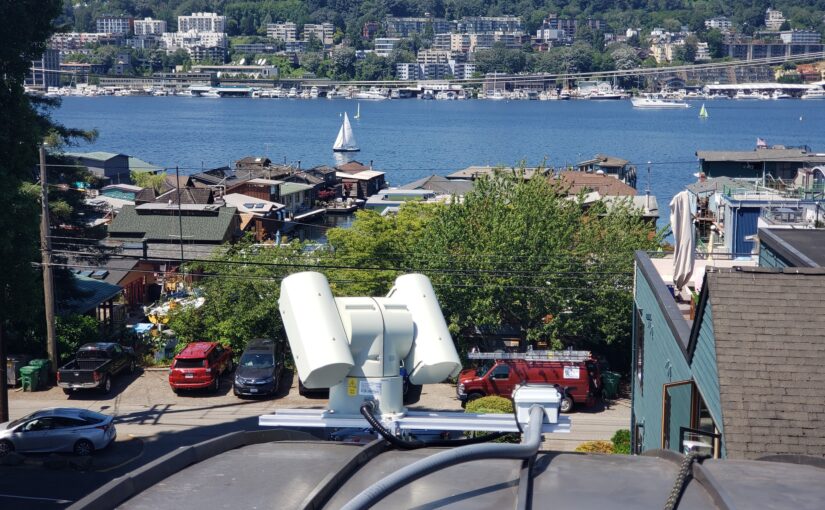

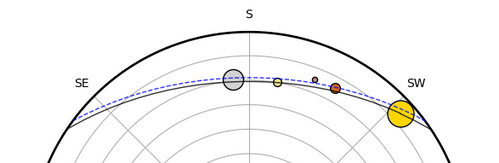

I had a lot of fun installing an industrial outdoor pan-tilt-zoom (PTZ) camera on my roof in Seattle. Whereas most townhouses built today have rooftop decks, my townhouse has a curved metal roof. Being near Lake Union, it has a phenomenal view from the top of the roof, showing the city, the lake, and even Gasworks park. Since it’s pretty difficult and unsafe to get up on that roof, I did the next best thing, which was to install a camera. This was inspired by this skybot cam post.

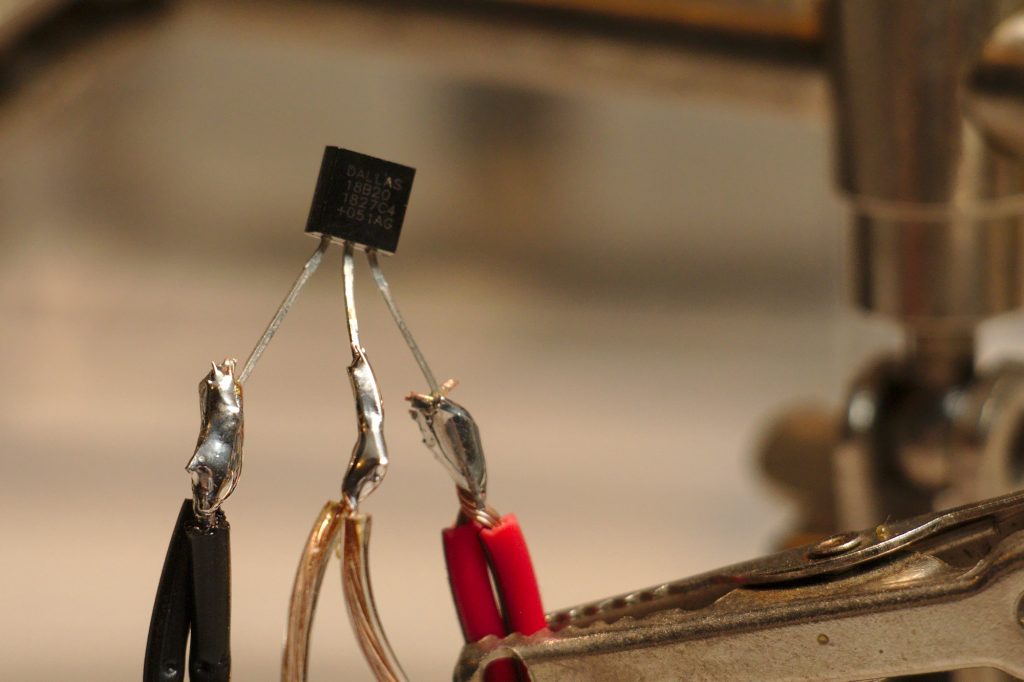

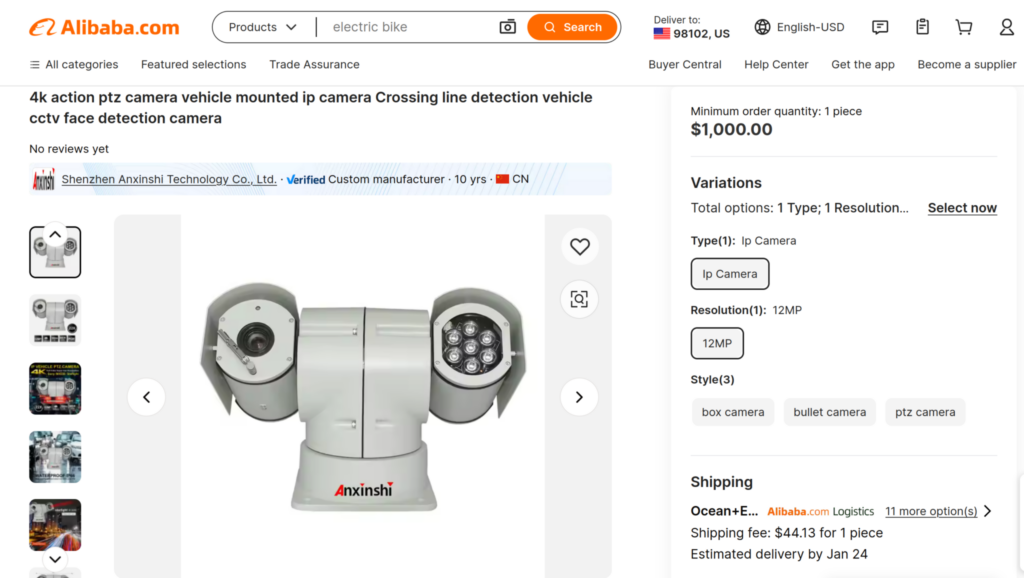

I spent a lot of time looking at camera options. New cameras from US vendors seem to be roughly $30k, which was way out of range. So I checked alibaba. Sure enough, there was a pretty awesome looking one with 4K resolution.

I was a little skeptical of how it would turn out, but was pleasantly surprised with the build quality and reliability. It showed up pretty quickly and I tested it out.

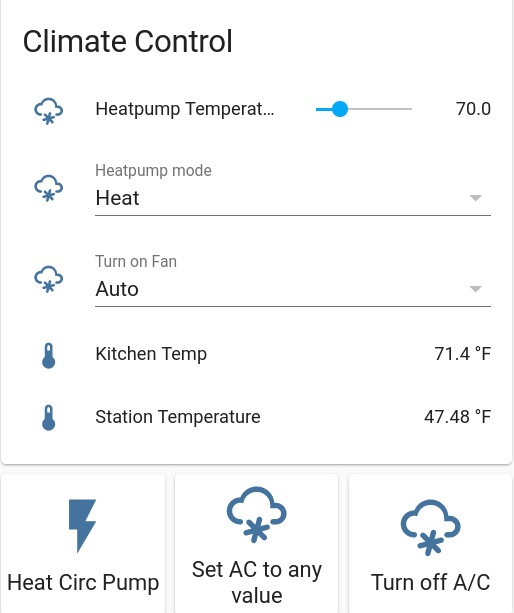

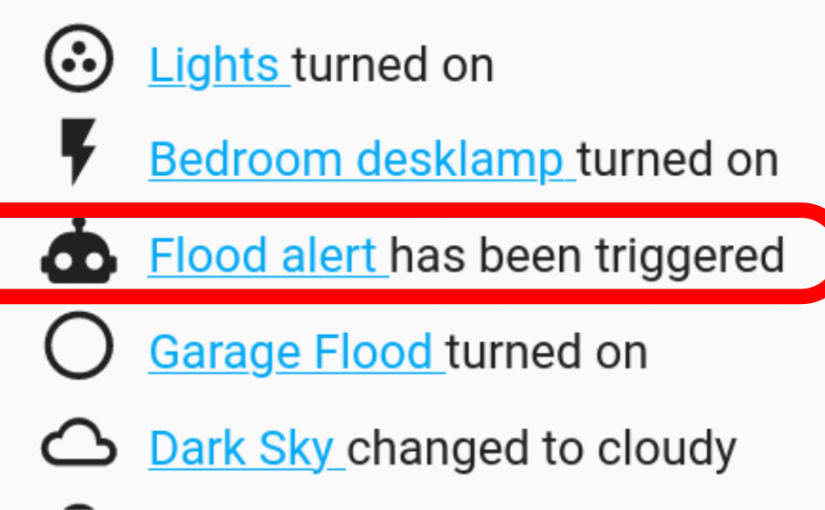

Getting into the firmware took a second because the password on the sticker was misspelled. I was able to figure it out and get in. The firmware was pretty solid with lots of cool features, and the camera supports basic ONVIF stuff so I can control it with standardized software, e.g. in Home Assistant via Frigate.

Continue reading The Eastlake Skycam