/*

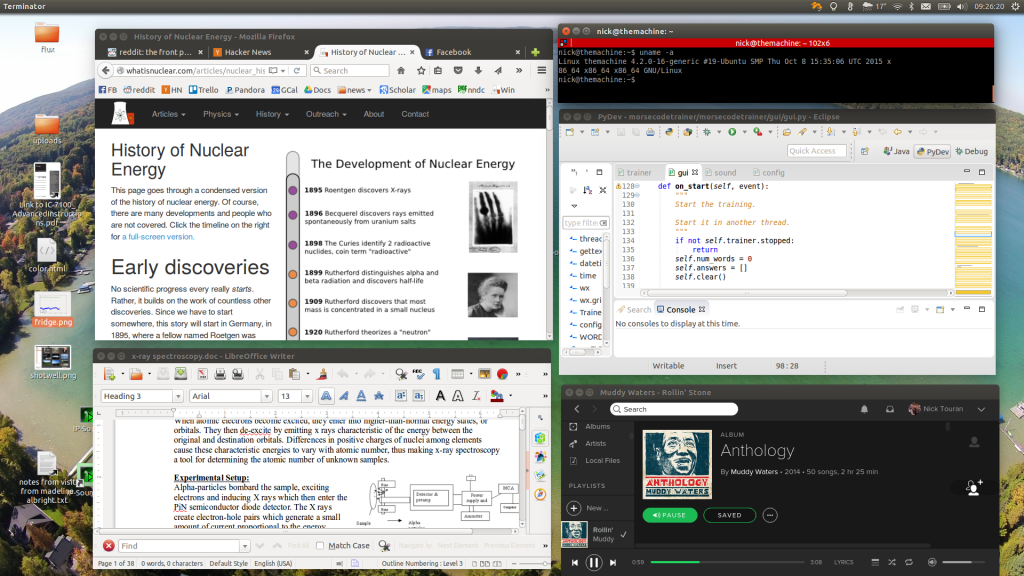

* Furnace Controller for ESP8266 and MQTT.

*

*

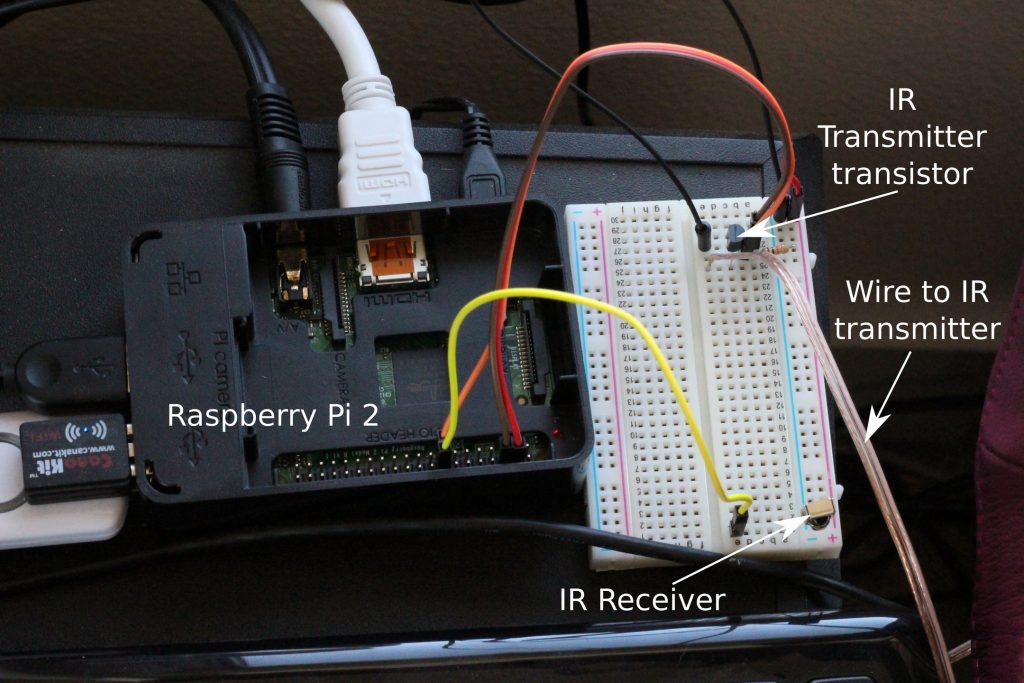

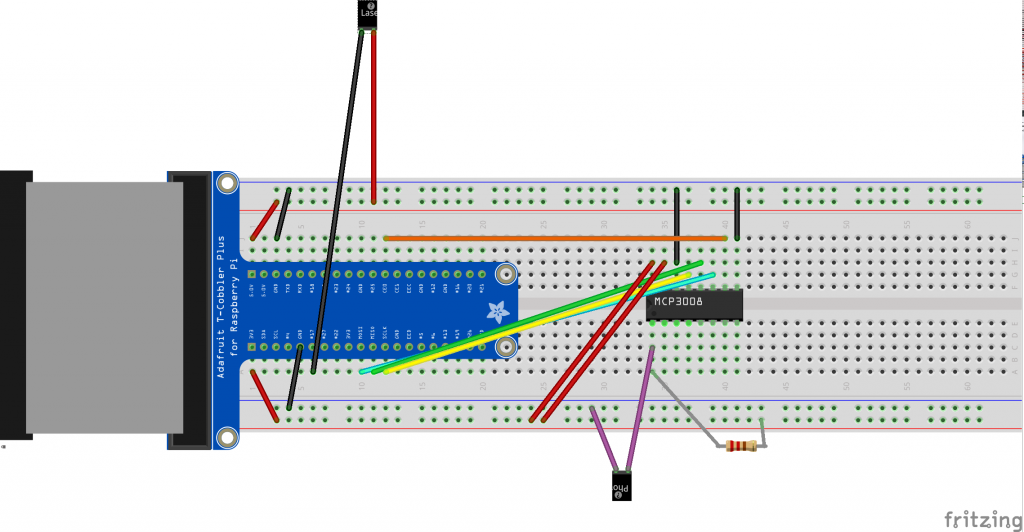

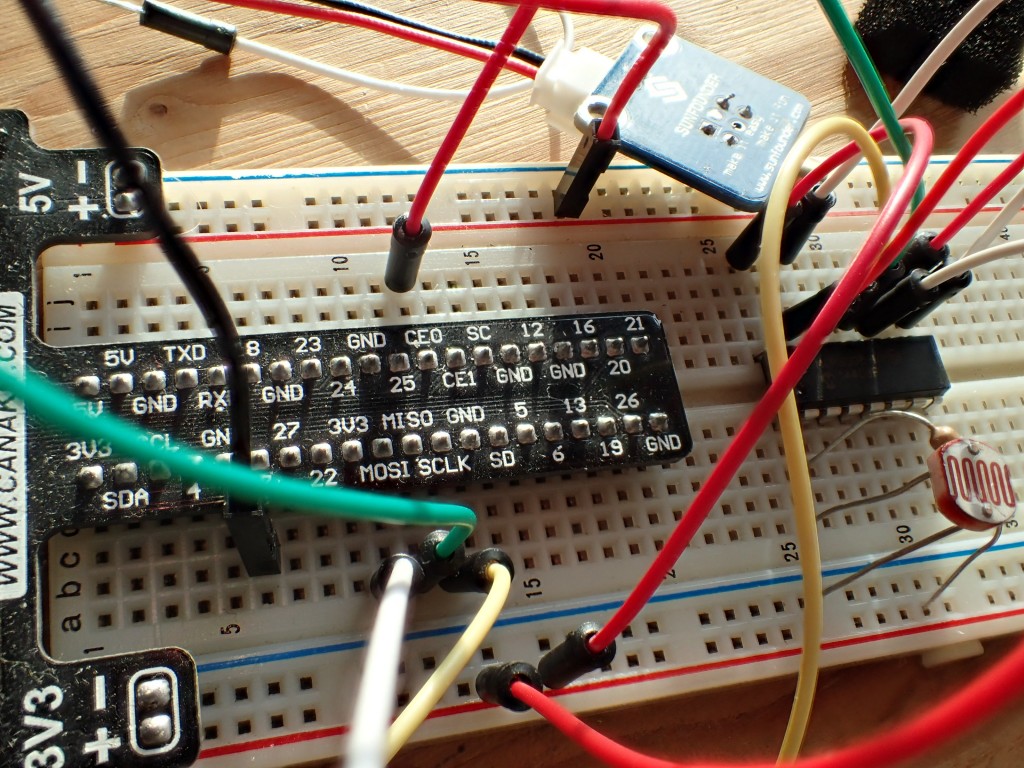

* Connections: GPIOs go to inputs, obviously. Connect 5V to VCC and jumper VCC to

* VCC-JD to power the coils. Note that GPIO HIGH corresponds to relay off with this

* board.

*

* D8 is a bad choice because it's actually GPIO 15 which messes things up during

* reboot.

*

* THE SOFTWARE IS PROVIDED "AS IS", WITHOUT WARRANTY OF ANY KIND, EXPRESS OR

* IMPLIED, INCLUDING BUT NOT LIMITED TO THE WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTABILITY,

* FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE, TITLE AND NON-INFRINGEMENT. IN NO EVENT

* SHALL THE COPYRIGHT HOLDERS OR ANYONE DISTRIBUTING THE SOFTWARE BE LIABLE FOR

* ANY DAMAGES OR OTHER LIABILITY, WHETHER IN CONTRACT, TORT OR OTHERWISE,

* ARISING FROM, OUT OF OR IN CONNECTION WITH THE SOFTWARE OR THE USE OR OTHER

* DEALINGS IN THE SOFTWARE.

*

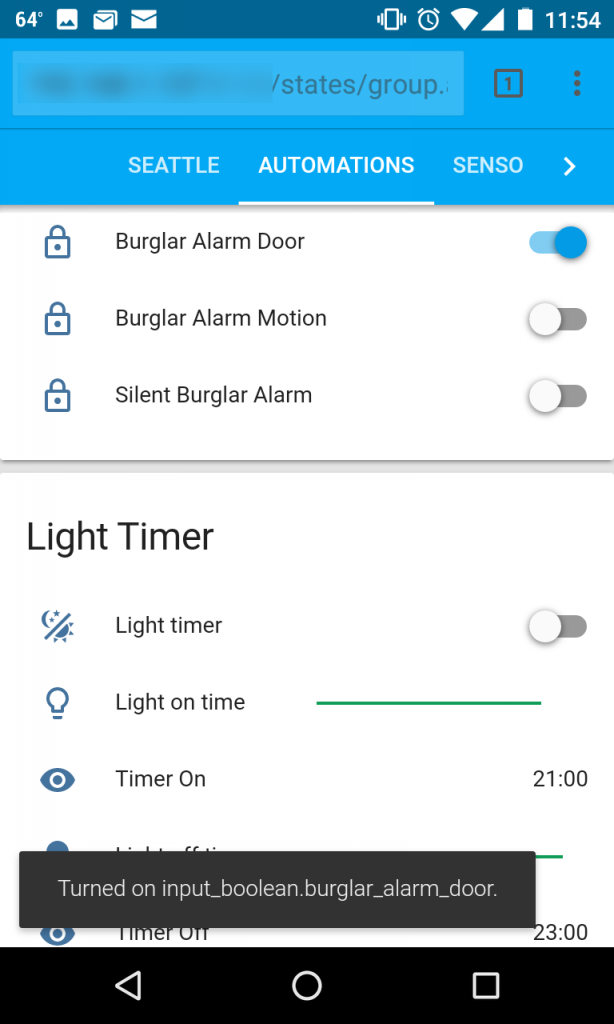

* Safety Features:

* 1. Should shut down if disconnected from internet (would be more robust

* with internal MQTT broker, but then couldn't message nick)

* 2. Should shut down if furnace pin has been on for a really long time.

* This could happen if the RPi/hass dies but the internet is still up.

*

* See https://partofthething.com/thoughts/enlighten-your-old-furnace-with-a-raspberry-pi-home-assistant-an-esp8266-and-some-relays/

*/

#include <ESP8266WiFi.h>

#include <ESP8266mDNS.h>

#include <WiFiUdp.h>

#include <ArduinoOTA.h>

#include <PubSubClient.h>

#define wifi_ssid "[redacted]"

#define wifi_password "[redacted]"

#define mqtt_server "[redacted]"

#define mqtt_user "[redacted]"

#define mqtt_password "[redacted]"

#define mqtt_error_topic "mom/status/furnace_error"

#define mqtt_status_topic "mom/status/furnace"

#define listen_topic "mom/furnace/#"

#define ota_password "[redacted]"

#define ota_hostname "[redacted]"

#define FOUR_HOURS 14400000 // milliseconds

#define NUM_PINS 6

#define FOUR_HOURS 14400000 // milliseconds

#define NUM_PINS 6

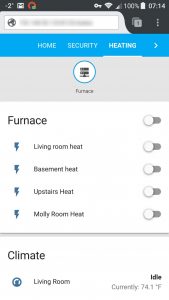

int MOLLY_PIN=D5;

int UPSTAIRS_PIN=D6;

int LIVING_ROOM_PIN=D7;

int BASEMENT_PIN=D4;

int NICK_BEDROOM=D1;

int DEN=D2;

int allPins[NUM_PINS] = {LIVING_ROOM_PIN, UPSTAIRS_PIN, MOLLY_PIN, BASEMENT_PIN, NICK_BEDROOM, DEN};

// track how long each pin has been on for auto-shutoff function

// (for when MQTT controller on Pi dies but net is up)

unsigned long onTime;

unsigned long now;

int numPinsOn = 0;

WiFiClientSecure espClient;

PubSubClient client(espClient);

void setup() {

Serial.begin(115200);

setup_gpio();

setup_wifi();

setup_mqtt();

setup_ota();

}

void setup_gpio() {

// Connect each relay pin to each GPIO.

// Hook +5V up to relay module.

for (int i=0;i<NUM_PINS+1;i++) {

pinMode(allPins[i], OUTPUT);

}

all_pins_off();

}

void all_pins_off() {

for (int i=0;i<NUM_PINS+1;i++) {

digitalWrite(allPins[i], HIGH);

}

numPinsOn = 0;

}

void setup_wifi() {

delay(10);

Serial.println();

Serial.print("Connecting to ");

Serial.println(wifi_ssid);

WiFi.mode(WIFI_STA);

WiFi.begin(wifi_ssid, wifi_password);

while (WiFi.status() != WL_CONNECTED) {

delay(500);

Serial.print(".");

}

Serial.println("");

Serial.println("WiFi connected");

Serial.println("IP address: ");

Serial.println(WiFi.localIP());

}

void callback(char* topic, byte* payload, unsigned int length) {

Serial.print("Command arrived [");

Serial.print(topic);

Serial.print("] ");

for (int i = 0; i < length; i++) {

Serial.print((char)payload[i]);

}

Serial.println();

// Switch on the heat if an 1 was received as first character

int pin = -1;

if(strcmp(topic,"mom/furnace/livingroom")==0) {

pin = LIVING_ROOM_PIN;

}

else if (strcmp(topic,"mom/furnace/upstairs")==0){

pin = UPSTAIRS_PIN;

}

else if (strcmp(topic,"mom/furnace/molly")==0) {

pin = MOLLY_PIN;

}

else if (strcmp(topic,"mom/furnace/basement")==0) {

pin = BASEMENT_PIN;

}

else if (strcmp(topic,"mom/furnace/nick_room")==0) {

pin = NICK_BEDROOM;

}

else if (strcmp(topic,"mom/furnace/den")==0) {

pin = DEN;

}

if (pin == -1){

Serial.print("Unknown Topic. Aborting command.\n");

return;

}

else {

Serial.print("Pin is ");

Serial.print(pin);

Serial.println();

}

if ((char)payload[0] == '1') {

Serial.print("Turning on");

digitalWrite(pin, LOW);

numPinsOn = 1; // will be a problem if we start doing more than 1 zone. Upgrade then.

onTime = millis(); // will roll over every 72 hours or so.

} else {

Serial.print("Turning off");

digitalWrite(pin, HIGH);

numPinsOn = 0;

}

}

void setup_mqtt() {

client.setServer(mqtt_server, 8883);

client.setCallback(callback);

}

void reconnect() {

// Loop until we're reconnected.

int reconnectAttempts = 0;

while (!client.connected()) {

Serial.print("Attempting MQTT connection...");

// Add a will message in case we get kicked offline for some reason.

if (client.connect("ESP8266Furnace", mqtt_user, mqtt_password, mqtt_status_topic,

1, 1, "0")) {

Serial.println("connected");

client.subscribe(listen_topic, 1); // important to get QoS of 1 to ensure message makes it.

client.publish(mqtt_status_topic, "1", true);

} else {

reconnectAttempts++;

Serial.print("failed, rc=");

Serial.print(client.state());

Serial.println(" try again in 5 seconds");

if (reconnectAttempts > 60) {

// If we cannot connect for a long time, shut off all pins. Internet is dead

// and we can't be controlled anymore. Fallback on manual thermostats at this point

// so we don't burn the house down.

all_pins_off();

client.publish(mqtt_error_topic, "1", true); // for sensing errors.

reconnectAttempts=0;

}

delay(5000); // Wait 5 seconds before retrying

}

}

Serial.print("MQTT connected.");

}

void setup_ota() {

ArduinoOTA.setPort(8266);

ArduinoOTA.setHostname(ota_hostname);

ArduinoOTA.setPassword(ota_password);

ArduinoOTA.onStart([]() {

Serial.println("Starting OTA update.");

all_pins_off();

});

ArduinoOTA.onEnd([]() {

Serial.println("\nOTA update ended.");

});

ArduinoOTA.onProgress([](unsigned int progress, unsigned int total) {

Serial.printf("OTA Progress: %u%%\r", (progress / (total / 100)));

});

ArduinoOTA.onError([](ota_error_t error) {

Serial.printf("Error[%u]: ", error);

if (error == OTA_AUTH_ERROR) Serial.println("Auth Failed");

else if (error == OTA_BEGIN_ERROR) Serial.println("Begin Failed");

else if (error == OTA_CONNECT_ERROR) Serial.println("Connect Failed");

else if (error == OTA_RECEIVE_ERROR) Serial.println("Receive Failed");

else if (error == OTA_END_ERROR) Serial.println("End Failed");

});

ArduinoOTA.begin();

}

void failsafe() {

// If any pin has been on for more than four hours it seems like something's wrong.

// Possibly the Rpi died and isn't sending an off signal.

// Granted, if a bunch of zones were coming on and off staggered, then

// this would have to be upgraded to get fancier.

now = millis();

if (numPinsOn > 0 && (now-onTime)> FOUR_HOURS) {

all_pins_off();

Serial.println("Seems stuck on. Rebooting.");

client.publish(mqtt_error_topic, "2", true); // for sensing errors.

ESP.restart();

}

}

void loop() {

if (!client.connected()) {

reconnect();

}

client.loop();

failsafe();

ArduinoOTA.handle();

delay(500);

}